Did public health really tell people COVID vaccines were 100% effective? Yes.

This is post 2 of 4 in this series looking back at the public health communication around the Covid-19 vaccines, why trust was lost, and where communication broke down. The goal is not to point fingers or lay blame, but rather get a view from outside our bubble to see how messages were perceived. Read the first post here.

Why did so many Americans expect an essentially perfect Covid-19 vaccine?

To be sure, the perfect vaccine is a strawman argument frequently used to discredit vaccination—only perfectly safe and perfectly effective vaccines are allegedly acceptable, and anything less is considered a failure.

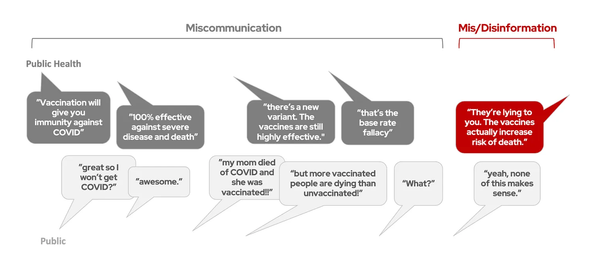

But for the COVID vaccines, there was more to this belief than strawman arguments. Many people who had gladly received a COVID vaccine felt confused and betrayed when breakthrough cases emerged. Looking back, it wasn’t just misinformation that confused people—well-intended public health messages and even miscommunication over the meaning of words set expectations far too high.

Problem #1: Expectation management

On June 30, 2020, the FDA released guidance on what standards COVID vaccines must meet to gain FDA authorization: 50% efficacy. And that’s not just efficacy against infection—even a 50% reduction of severe disease or death would have met the FDA’s threshold. Dr. Fauci said a vaccine with 70% or 75% efficacy would be “terrific.”

Were the public’s expectations set? No. There was so much other pandemic news—hospitals were overloaded, new rumors were popping up daily, and we were going 2,000 mph trying to keep up with communicating to the public. We didn’t know if we would get a vaccine in six months or three years, never mind the details about how well it would work. Setting the public’s expectations about vaccine efficacy and anticipating concerns was, understandably (but mistakenly), much lower on the priority list than the biotechnology itself.

Better than we dared to hope

Then, in late 2020, expectations were blown out of the water. The results of the Moderna and Pfizer trials came out: not one, but two vaccines with OVER 90% EFFICACY!!! It cannot be overstated just how good this news was. Over 300,000 people had died from COVID-19 in the U.S., and finally, some hope was on the horizon.

Very good. But not perfect.

Amid this fully justified enthusiasm, the groundwork was laid for a communication blunder that later left many feeling confused and betrayed.

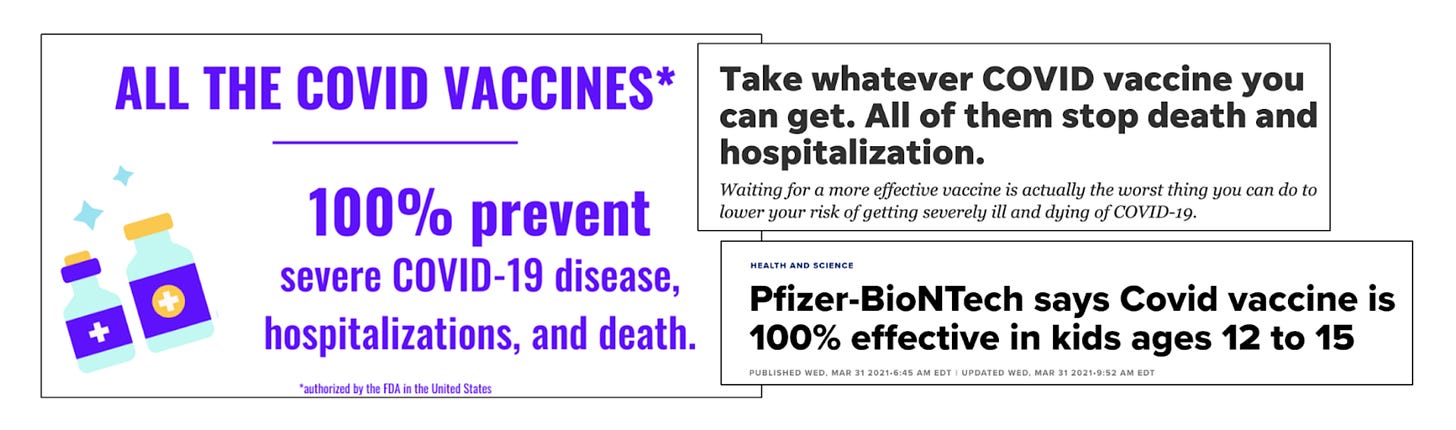

The >90% efficacy above referred to efficacy against symptomatic infection. A second outcome was also reported: 100% efficacy against severe disease and death. In reality, the clinical trials were not big enough to accurately measure this—they were statistically powered around symptomatic COVID-19 infection, not hospitalization or death. This “100%” number was a ballpark, not a precise estimate.

But soon, it became a widely circulated talking point. To encourage people to take the first vaccine available to them and not wait for their favorite vaccine, people were reminded: all three COVID vaccines were 100% efficacious in preventing severe disease and death.

The public’s expectations were set: 100% efficacy was what they were promised. To make matters worse, messaging started mixing up the data regarding symptomatic infection and severe disease/death, leading to public’s assumption of a foolproof vaccine.

Problem #2: Two different definitions of “immunity”

Adding to this confusion was the word “immunity.” In science, immunity describes one of humankind’s most complicated biological systems. There are multiple types of immunity, and the degree of immunity someone has can vary dramatically depending on a wide variety of factors.

But in everyday language, “immunity” often implies something much simpler: complete protection from something. As one person in an informal poll put it, “Immunity is like in a zombie movie, when you can be right next to the zombies and they can’t get you.”

Experiences with childhood vaccinations reinforce this simpler interpretation of immunity as perfect protection. Rates of diseases like polio are extremely low for vaccinated people in the U.S. for two reasons: the vaccines have high (but not perfect) efficacy, and people are unlikely to encounter those diseases in the first place due to herd immunity from vaccination.

For many, this leaves the impression that immunity from vaccination = you’re not gonna catch the disease, ever. The hidden effect of herd immunity makes those childhood vaccines seem essentially perfect.

Enter the COVID vaccines. People were told it gives them “immunity,” and they expected immunity like they were accustomed to—essentially no risk of catching the disease, at all. Video game immunity, a flawless shield of protection. Hearing COVID vaccines provided “100% protection” reinforced this belief.

Reality

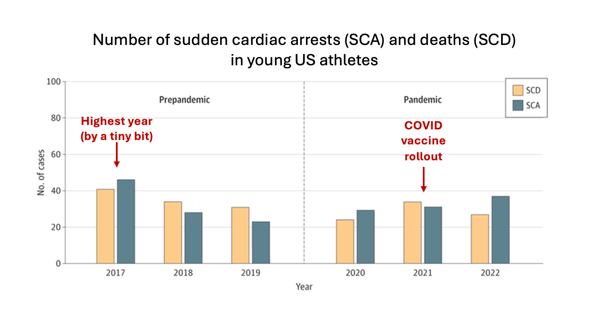

Of course, like all vaccines, the COVID vaccines were not perfect. And we didn’t have herd immunity. By summer 2021, COVID was everywhere—a vaccine can be even 99.9% effective, but if nearly everyone is getting exposed, breakthrough infections are going to happen in the thousands. (If this measles outbreak continues to grow, we'll see the same thing – breakthough infections in vaccinated people). Waning immunity meant that >90% efficacy did not stick around forever, and new variants kept coming to town, partially evading the vaccine’s defenses. While some did try to warn about the possibility of new variants and waning immunity, the easy and simple messaging of “100% effective,” reinforced by the belief that immunity meant essentially perfect protection, was so much louder.

“These must not be vaccines”

When breakthrough infections started to happen, many believed they had been misled—they were expecting nearly perfect immunity, and that is not what they got. Vaccines, they knew, were supposed to protect them, so this led to the rumor that the COVID vaccines aren’t actually vaccines.

Failure or success?

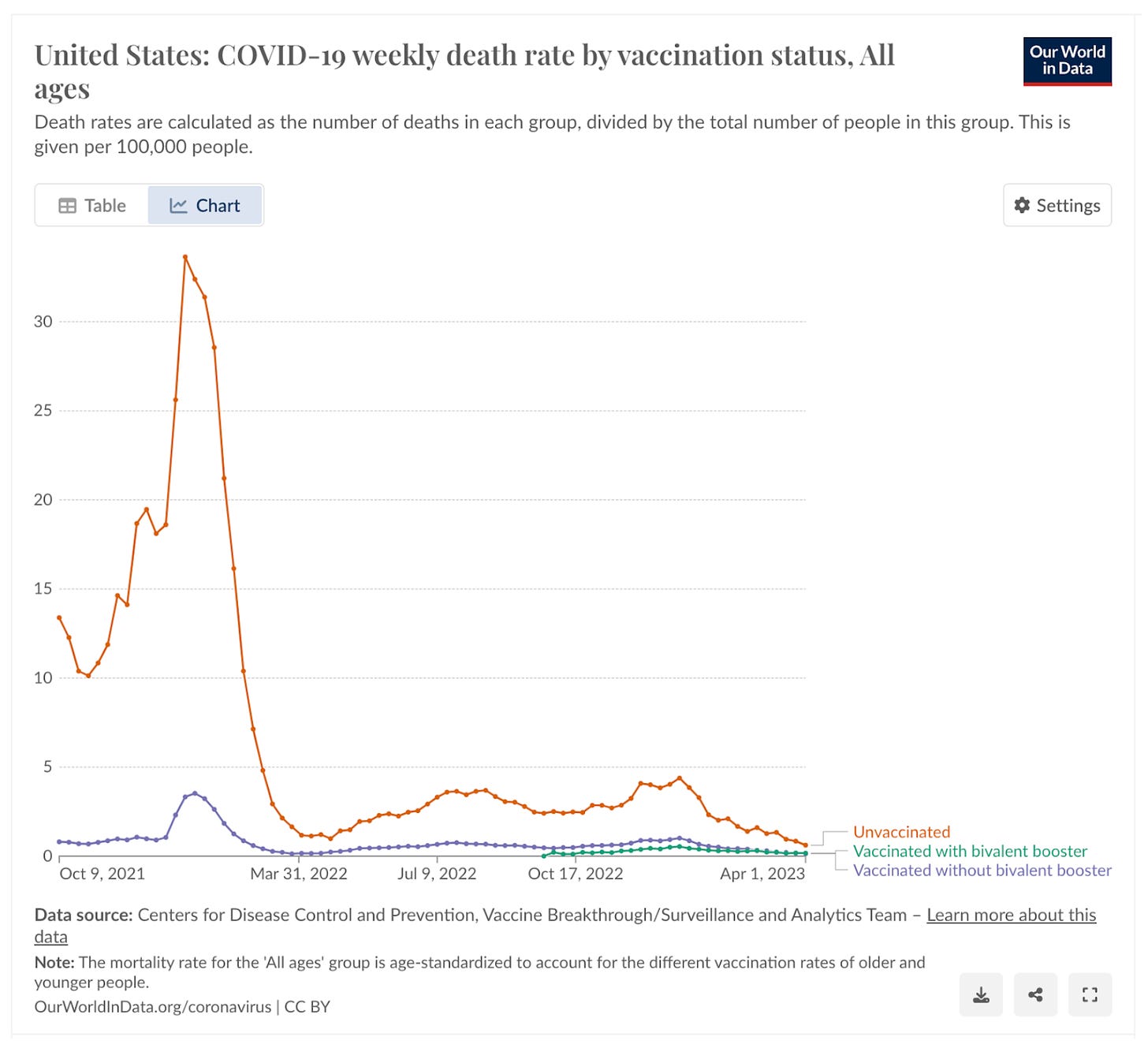

The vaccines were saving hundreds of thousands of lives, but weren’t quite as good as they initially seemed. Public health stuck to the first part: reinforcing the dramatic effect of vaccination on reducing severe illness and death. But many in the public felt betrayed by the second part: they were promised something even better—100% protection = 0 risk of death. When people brought that up, many were ignored or dismissed, or even worse: chastised for not understanding immunology and spreading misinformation.

How to do better next time

- Communicate uncertainty in what we do and don’t know. Avoid promising 100%—it is a promise we can rarely keep.

- Realize words like “vaccine-preventable disease,” “immunity,” “prevents,” and “works” are frequently misinterpreted to mean essentially perfect protection, and be careful using them.

- Recognize that odd rumors like “the COVID vaccines aren’t actually vaccines” are often a sign of genuine confusion—that people don’t understand the messages we’re telling them.

- Set expectations, loudly. And don’t be afraid to say vaccines aren’t perfect.

Early messaging about the COVID vaccines and confusion over vaccine immunity set the public’s expectations far too high, leading to profound disappointment down the road. To earn and keep the public’s trust, we need to avoid overly simple messaging and communicate uncertainty, especially during a rapidly developing public health crisis.

A version of this article was originally published on Your Local Epidemiologist.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things and author of Your Local Epidemiologist’s section on Health (Mis)communication. You can subscribe to her website below or find her on Substack, Instagram, or Bluesky. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.