What do we do when experts disagree?

A friend of mine recently asked me how I respond to people who have opposing views about scientific issues like vaccines, and as evidence they cite people with credentials (i.e. PhDs, MDs) who agree with their position. This is a great question, and something I encounter all the time. Here are my thoughts.

Do credentials matter? On one hand, yes they do, because somebody who has gone through medical school has much more training in medicine than someone who has never taken care of a patient. Likewise, someone who has a PhD in the biological sciences has much more training in interpreting biological research studies than someone who has never done research before. So training matters, and credentials are a mark of training.

On the other hand, people can hold advanced degrees and still be very wrong. And if we blindly believe someone because they have an MD or PhD, what happens when another MD or PhD disagrees with them? We are at an impasse. The idea that the person with higher scientific credentials must be right is a logical fallacy called the appeal to authority fallacy. It is not always true that the person with higher credentials is correct; reality does not bend to the will or whims of experts.

So, if one expert says one thing and another says the opposite, what do you do? Right now I think this one is especially confusing, because the scientific community says “trust the experts!” but then when an expert says something a bit weird, they say “ignore them!” The rules of science are this: the best data and the best analysis win. It does not matter who is saying it; the data and analysis are all that really matter. Often, scientists with more credentials are better at recognizing good data and analysis, so that is why it usually makes sense to “trust the experts!” But sometimes, an expert or two might latch onto bad data for a variety of reasons (they got overly attached to their hypothesis and want to be right, they have a financial conflict of interest, the science conflicts with their ideological views, they need an audience, they are speaking outside their area of expertise). In these cases, it is best to ignore them.

So how do you handle this? The ideal way is to go look at the data for yourself. Unfortunately, effectively interpreting scientific literature requires a lot of training, and it is not a task I would put on someone who does not have a science or medical background. When people without the prerequisite scientific and medical training go and research a topic, usually what ends up happening is they read other people’s simplified interpretations and summaries of the data, rather than diving in the data for themselves. So they are not doing research in the scientific sense; rather they are gathering simplified summaries provided by other people (which are sometimes mixed with a large serving of opinion and speculation). This is through no fault of their own, as interpreting scientific data takes a lot of background knowledge and practice, and is not easily learned without formal training.

Does that mean people without a science or medical background should just give up? Not at all. I do recommend people “do their research” and read other people’s simplified summaries and interpretations. But as they do so, it’s important to recognize that they are not interpreting the primary data for themselves and rather are choosing which experts to trust and which experts to ignore. Sometimes when a person decides which expert to trust, that decision may be influenced by factors other than the expert’s credentials or the validity of their argument. For example, maybe someone trusts a scientist because what they’re saying also happens to align with their political views, and their summary of the science is more appealing. This can happen on both sides of the political aisle.

Second, when trying to figure out what’s true, I would recommend taking into account what the majority of scientists are saying — often this will lead you to the right answer. If there are 10 doctors saying one thing and there are 10,000 doctors saying a different thing, chances are the 10,000 doctors are right. There are of course some cases in history where the 10,000 doctors were wrong, but those are the exceptions, and ultimately the lone crazy ones won them over with the data.

So to get back to my friend’s question, how would I respond to someone who is arguing a scientific point that is false but cites credentialed scientists who support that view? First, I try to get more information on what that scientist is saying. Sometimes there are legitimate points, and then we have some common ground to agree upon. But sometimes the statements of the scientist are completely baseless. In those cases, I try to focus more on the data and the rationale behind the arguments, rather than a battle of which credentialed person carries more weight.

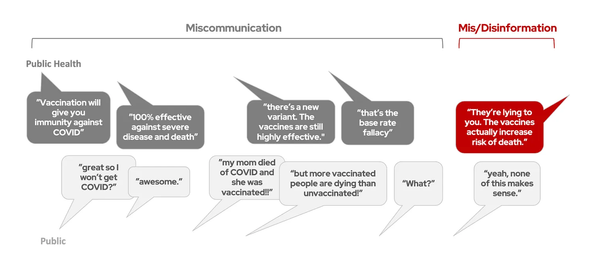

But it’s also important to remember that the major issue behind these arguments often isn’t about data or credentials; it’s about trust. Many people simply don’t trust the CDC, the WHO, and other institutions, and are looking for other experts whom they feel are more trustworthy. Someone can bring all the data and reasoned arguments in the world, but if there isn’t any trust there, it’s probably not going to do much.