Trust issues: public health in a NYC comedy club

Last week I hopped on the train down to NYC to attend one of the most unusual and enjoyable events I have ever attended in my academic career.

A comedian, podcast host, and epidemiologist walked into a bar, and they dished out some tough love to the public health community.

The event was "Trust Issues: A night of laughter with serious side effects" hosted by my good friend Katelyn Jetelina, author of the internationally renowned substack Your Local Epidemiologist. She was joined by Brinda Adhikari, writer and producer for Jon Stewart and co-host of Why Should I Trust You?, a new podcast that has in-depth conversations with people who profoundly distrust public health. Comedian Casey Balsham opened with a killer set and reminded us to stop taking ourselves so seriously.

It's not often an epidemiologist can sell out a comedy club, but she did, with a line out the door. And it was well worth the trip. The audience included national news correspondents, writers for the New York Times, senior leaders in the national COVID response efforts, and many more.

The problem: a crisis of trust in science

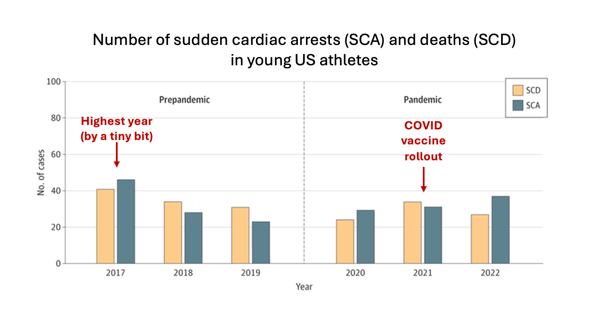

Ever since the COVID pandemic, scientists and public health leaders have been sounding the alarm about the declining trust in science. Every academic knows it's a giant problem, and we're now bearing the fruit – funding cuts to science and health institutions, nomination of leaders with a track-record of ignoring evidence-based practice, and poll after poll showing declining public trust in our health institutions.

The response from the scientific community has been largely to blame misinformation and those spreading it. Conversations generally center around how scientists are right and those who distrust them are wrong, and we just need to get them to see the facts and understand that misinformation has misled them.

But clearly, this approach hasn't worked (see Figure 1).

A different approach to the trust crisis

Public health needs a radical change to our communication approach. Calling out misinformation over and over again and shaming those who believe it will not work. Our public health infrastructure is actively being dismantled, and many Americans find this to be a welcome change. Very few people are reaching across the aisle to ask why – why don't you trust public health? And what should we do differently?

That's what this night was about. I wish I had a whole transcript to share with you, but here are the highlights:

- Embrace radical listening. The core reasons behind distrust often run deeper than scientific facts – they're about values, shame, and insults people have experienced. Brinda encouraged us to take the approach she and her co-hosts have on their podcast, which is to shut up and listen (my paraphrase) to people who deeply distrust public health, resisting the urge to fact-check them and instead genuinely trying to understand their view. When you do that, you will discover that underneath the false scientific beliefs that drive scientists crazy is a person who has been deeply hurt by past experiences with our health institutions, such as doctors who dismissed them, a medical system that couldn't find the answers they needed, or messaging about vaccines that called them selfish and stupid. The goal is not to agree on everything, but to find genuine empathy. Once you do that, you can stop lecturing and start rebuilding bridges.

- Stop using the word "misinformation." For many Americans, the words "misinformation" and "disinformation" have become synonymous with censorship and a narrative they're not allowed to question. (I would add "fact-check" and "debunk" to that list). Brinda recommended we stop using "misinformation" as it starts off the conversation by telling someone they are misinformed, which isn't the greatest intro for trust building. It's critical we know our audiences – in academic circles these words are welcome, but outside of academia, these words will alienate many we are trying to reach.

- People first, science second. We know that an evidence-based approach is the best way to keep people healthy, and it's so easy to elevate the data and evidence-based recommendations as the most important thing. But that leads us to paradoxes, such as caring more about whether or not someone is vaccinated than actually caring about them as a person. It can also cause us to rally around institutions like the NIH and CDC, instead of the causes those institutions are meant to serve. Fundamentally, public health and biomedical research are about helping people, and we have to keep that front and center. Calls to restore NIH funding will be ignored by many; stories of how research breakthroughs saved the life of a child will reach far more.

A final thought from me

At the end of the night, Katelyn and I were chatting about just how hard this new approach will be. The scientific community has justified anger, if not rage, at the situation unfolding around us – people are losing their jobs, decades-long research efforts are being cut, critical infrastructure is being defunded, and the ability to train the next generation of scientists is in jeopardy. Even more than that, the proliferation of false information in many ways feels like an assault on reason – the very basis by which we figure out what is real and true is being undermined by anecdotes and fear. The public health world has been traumatized, first by COVID, and now by efforts to undermine the infrastructure critical to doing their jobs. It's not easy to find empathy for the people cheering on the destruction of what so many have spent their careers building.

But ironically, the evidence-based path to restore trust in science is exactly that – empathy. It's the secret sauce that will fix this. The need to vent and process the trauma is real; do it. Then when you're ready, start listening.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things and author of Your Local Epidemiologist’s section on Health (Mis)communication. You can subscribe to her website below or find her on Substack, Instagram, or Bluesky. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.