Why criticizing "anti-vaxxers" often backfires

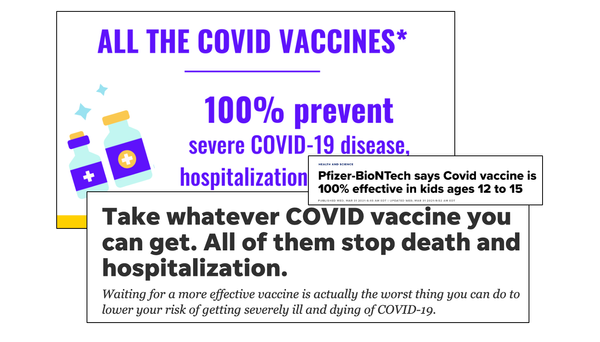

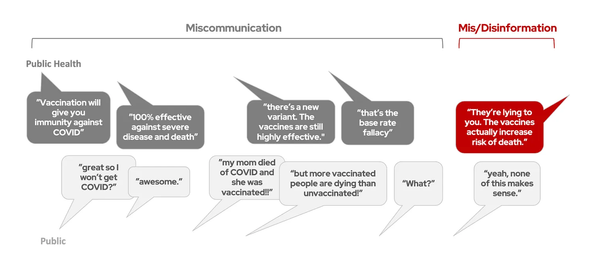

This is post 3 of 4 looking back at the public health communication around the COVID vaccines and why trust in vaccines was damaged. Catch up on the first two posts: misinformation versus miscommunication and expectation management.

Shame doesn’t work, but has become widely adopted as a response to vaccine hesitancy.

“Denormalizing”—the process of reinforcing a negative behavior as socially unacceptable, can be beneficial, and has proven successful in public health efforts such as campaigns to reduce smoking. However, it’s a double-edged sword—efforts to denormalize a behavior can lead to shame and stigma, which don’t help. We know from the literature around smoking and alcohol use that shame and stigma not only don’t work, but often backfire. One study found exposure to negative stereotypes about smoking actually increased the drive to smoke.

Denormalization can help, but shame can cause harm. Where is the line?

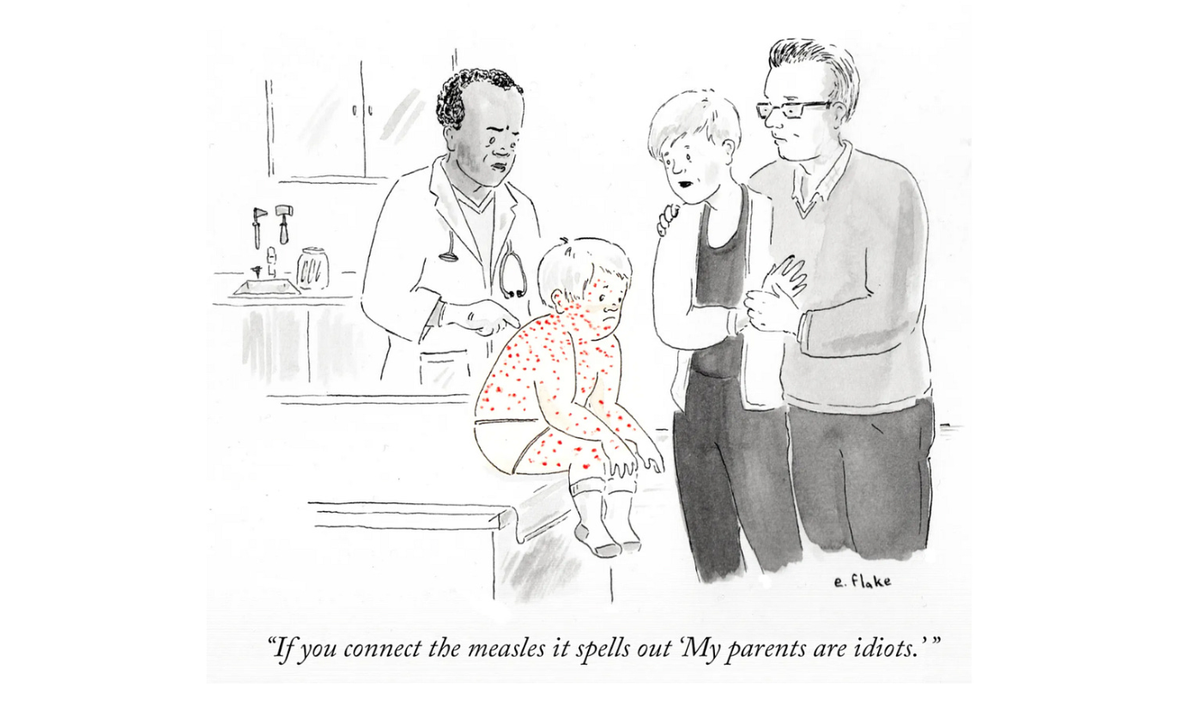

Renowned shame researcher Brené Brown draws a distinction between shame and guilt that helps clarify: guilt says I’ve done something bad, shame says I am bad. Guilt is helpful—it reveals when behaviors need to change. Shame, on the other hand, smothers us. It employs the ad hominem fallacy—instead of addressing an argument or behavior, it attacks the person themselves.

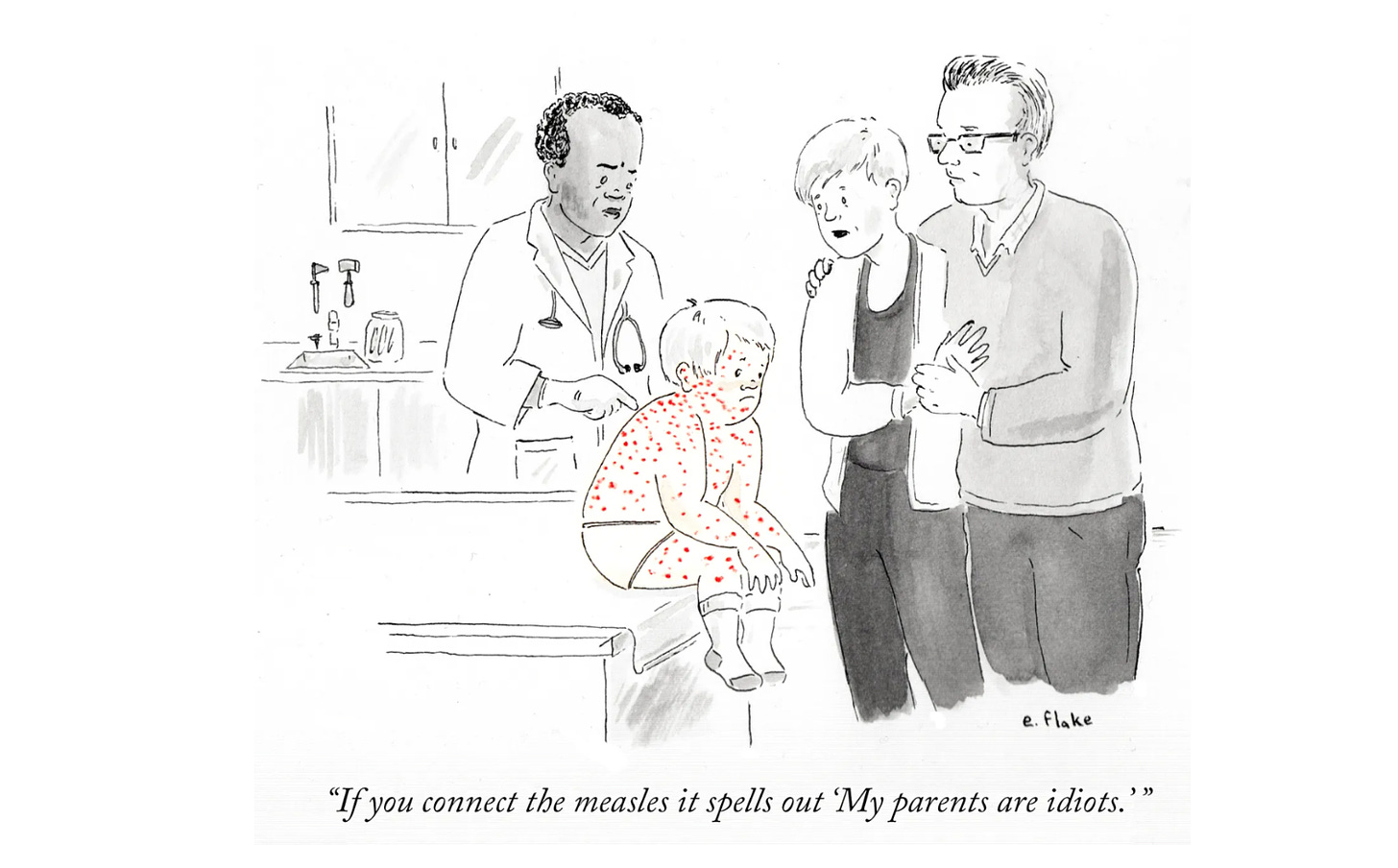

Guilt says: this was the wrong decision. Shame says: you are idiots.

Shame has, unfortunately, been widely adopted as a strategy to combat vaccine hesitancy. An analysis of TikTok videos about vaccines revealed that videos promoting vaccines overall used more negative language and more judgment, while “anti-vax” videos used more positive language and had higher levels of positive appreciation and emotion. In particular, they found pro-vaccine videos sometimes labeled “anti-vaxxers as weak, stupid, fragile, selfish, or crazy and their behaviour as insane or dumb.”

In my own experience, I’ve found this to be true—while I’ve had my fair share of awful comments from people opposing vaccines, I’ve found some of the pro-vaccine comments can also be extremely vicious. For example, I’ve had to delete comments off my Instagram posts from pro-vaccine advocates telling those who distrust vaccines to go kill themselves.

Of course, these extreme vicious comments are the minority, but the ad hominem sentiment that “anti-vaxxers are stupid” has become mainstream, featured in headlines and late-night talk show segments.

Is this strategy working? No, it’s making things worse

While often a well-intentioned effort to combat inaccurate information about vaccines, shame-based or “mean” messaging backfires. This is intuitive: we generally don’t take advice from people who treat us with contempt and disgust, even if they have credentials. This is also backed up by data:

- In a study conducted during the COVID vaccine rollout, perceived ‘moral reproach’ (feeling morally judged for not being vaccinated against COVID) did not motivate people to get vaccinated, and instead did the opposite—it strongly predicted vaccine refusal.

- A study using natural language processing of Twitter conversations found that corrections to inaccurate information that used positive and polite language were more likely to be effective, whereas corrections that used negative language (calling someone an idiot) were more likely to backfire, further entrenching the recipient in their belief.

Rants get views, and it’s easy to confuse virality with effectiveness. Social media content bashing people who reject vaccines is often popular because people who already trust vaccines cheer it on. But is this helping reach the people who actually need to be reached? Probably not, and if they do see it, the data suggests it will make them more hesitant about vaccines, not less.

It’s less about facts and more about values

Shame-based messaging ignores a critical dynamic in vaccine hesitancy: vaccine refusal isn’t just about intelligence or lack of understanding of facts and data. Often it has far more to do with people’s values and identity.

Katherine Hayhoe, internationally recognized climate scientist and science communicator, recommends when talking about climate change, the solution is not just showing people more and more data. Instead, she recommends connecting over values they already hold dear. This allows them to incorporate new information into their worldview instead of trying to change a core piece of who they are.

Shame-based messaging does the opposite: instead of connecting with a person’s identity and values, it attacks them.

Why is it so tempting to shame?

A lot of shame-based messaging is driven out of genuine, valid frustration. Just like those rejecting vaccines are not “bad” humans, those shaming them are not “bad” people either. (That would be shaming people for shaming people! Also not helpful.)

Where is this frustration coming from? There are the obvious answers—rejecting vaccines puts both the person and the community at higher risk of disease and leads to worse health outcomes, etc.

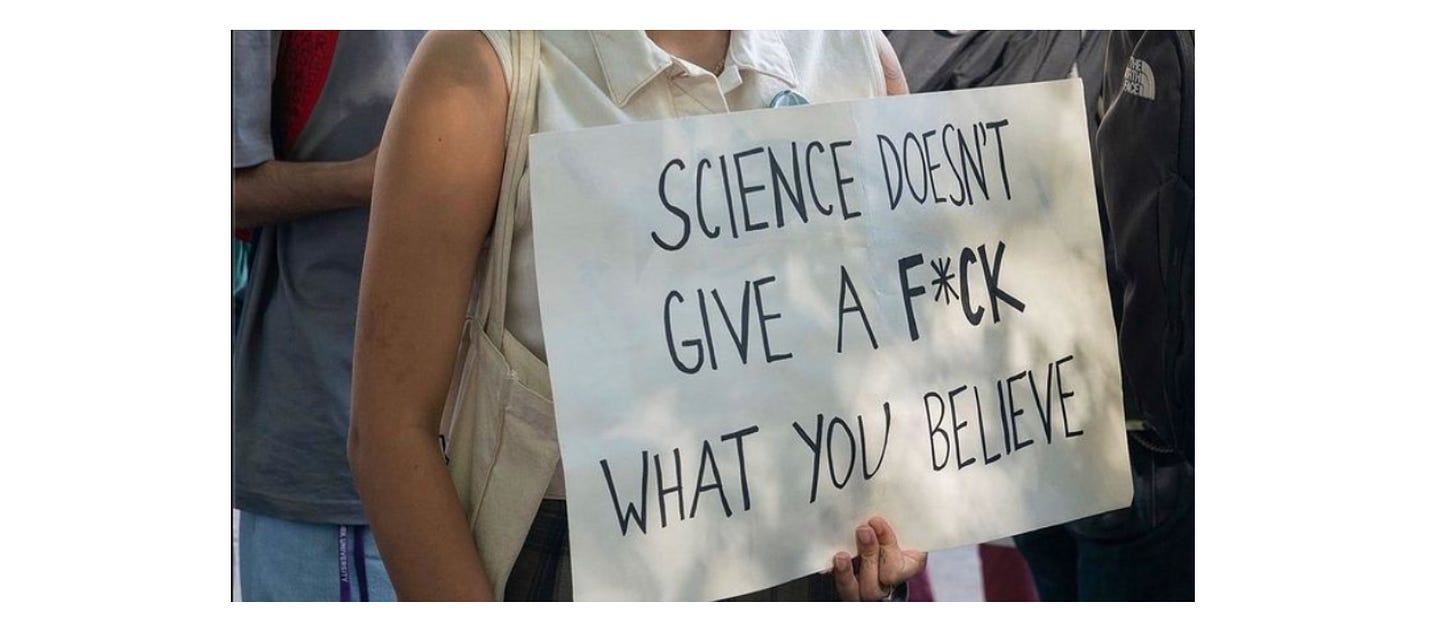

But early on in the pandemic, I realized for me (and probably many of you), it was more than that. It wasn’t just about the individual vaccines. It was fundamentally about believing that evidence-based medicine actually works—that systematically collecting data and analyzing it will give us a clearer picture of reality than anecdotes. That we don’t have to go back to the days of basing medical decisions on hunches, fears, and vibes. We have a better way of figuring out what’s real and true.

This frustration was perfectly encapsulated in a recent episode of The Pitt, an exceptional new medical drama which shows the reality emergency medicine doctors and nurses face on a daily basis (as an ER doc, can confirm it’s legit).

The rejection of carefully collected, peer-reviewed data in favor of rumors, anecdotes, and quick google searches is understandably exasperating. For those in science, medicine, and public health, it makes sense that this gets under our skin and infuriates us. For doctors, being attacked as incompetent or "pharma shills" for trying to give the best medical care possible to our patients, on top of dealing with the dysfunctional realities of our health care system, is demoralizing. (The Pitt tells this story well – watch the whole series).

But in the irony of ironies, reacting out of anger to defend evidence-based medicine is, itself, very much not evidence-based. Unfortunately, it will only make things worse, furthering the very problem we are trying to fix.

How to do better going forward

- Focus criticism on the data, not the person. It’s perfectly valid to criticize false beliefs and misleading data about vaccines. But when doing it, make sure your criticism focuses on the data and argument, not the person themselves.

- Rant privately. The need to vent your anger is real, do it. But not online—it might entertain those who already agree, but alienate those who we most need to reach.

- Kindness will get you further than anger. In defending the data, remember the data: kindness helps, insults do not.

- Connect over shared values. People will be far more open to what you have to say if you connect over values you both hold dear. Make sure you care more about the person than their vaccination status.

We must use science to figure out how to improve trust in science. And the science is clear: shaming isn’t helpful. Kindness, empathy, and connecting over shared values are the evidence-based path forward. This might not make us go viral, but it will build bridges instead of destroying them.

A version of this article was originally published on Your Local Epidemiologist.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things and author of Your Local Epidemiologist’s section on Health (Mis)communication. You can subscribe to her website below or find her on Substack, Instagram, or Bluesky. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.

Thanks to a wonderful community of readers, this newsletter is crowdfunded to keep science information free and accessible to all. If you’d like to be part of it, you can support this effort here: