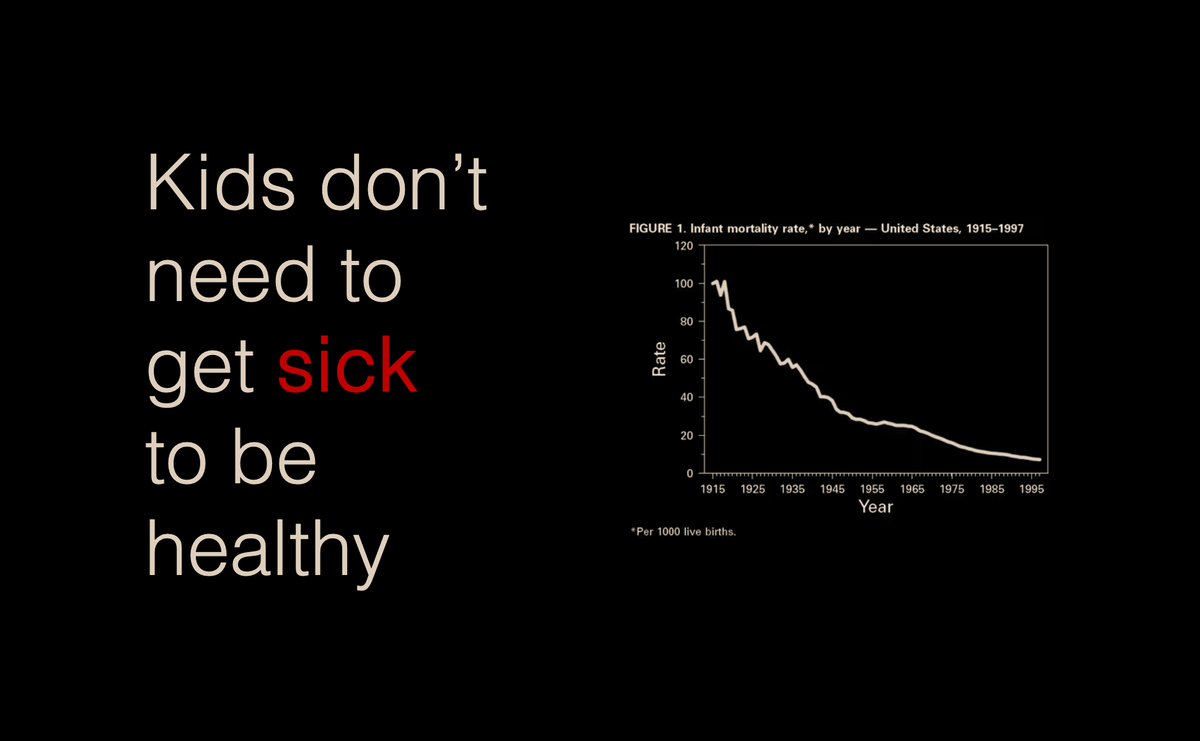

Kids don't need to get sick to be healthy

The 'Make America Healthy Again' movement is tapping into the commonly held belief that children in our modern era are less healthy than they used to be. Fueling this sentiment is the 'Hygiene Hypothesis' – an idea postulated in the 1980's that modern, overly sterile environments are harmful, and exposure to infections in childhood is good for immune development.

There is some truth to these sentiments—metabolic diseases like diabetes are on the rise, for example, which has profound impacts on long-term health. And it's true that exposure to germs matters (though which germs matters even more).

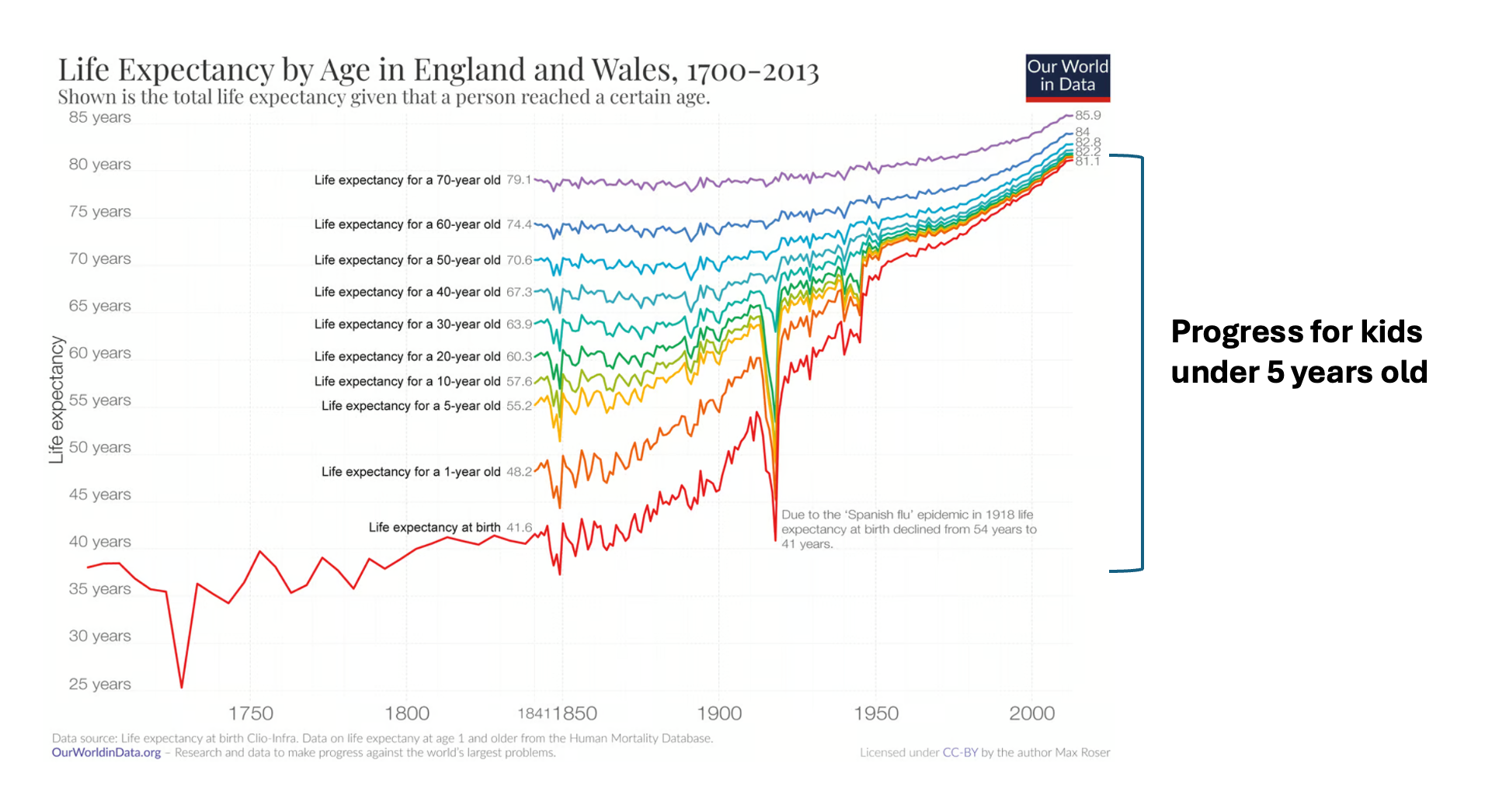

But, we also have to recognize the remarkable progress that has been made. Our modern era is an anomaly, in a good way, when it comes to the ultimate marker of childhood health: not dying.

The mythical “good old days”—when children had flourishing immune systems from their natural lifestyles and didn’t need antibiotics or vaccines—simply did not exist. Back in those days, a lot of children died.

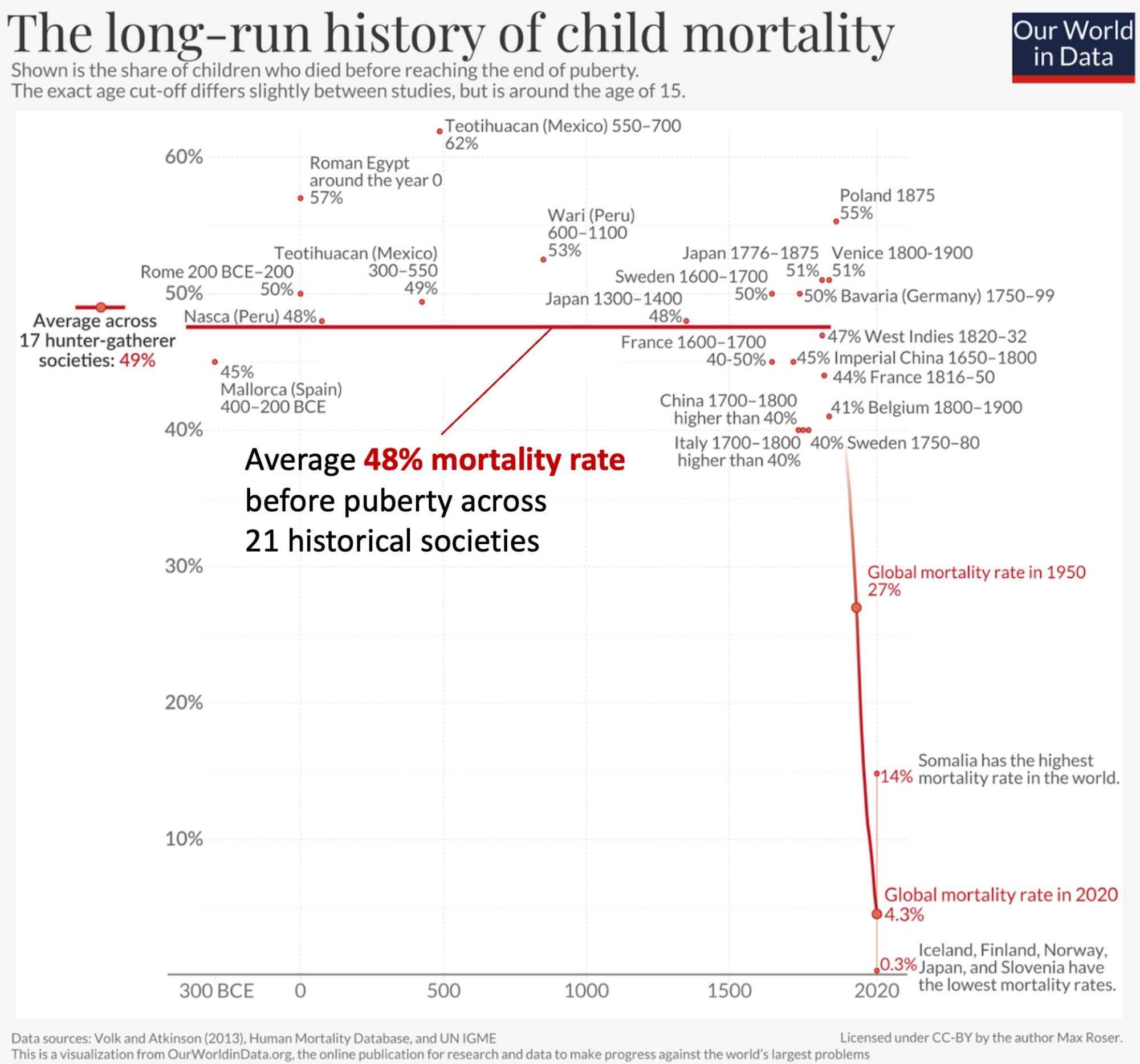

We have forgotten how many children used to die before their fifth birthday.

Today, the death of a child is considered unusual and especially tragic. For nearly all of history, this wasn’t the case. Death of children was extremely common. Until about the 1800s, roughly half of children died before reaching puberty. In a family of four children, on average only two would survive.

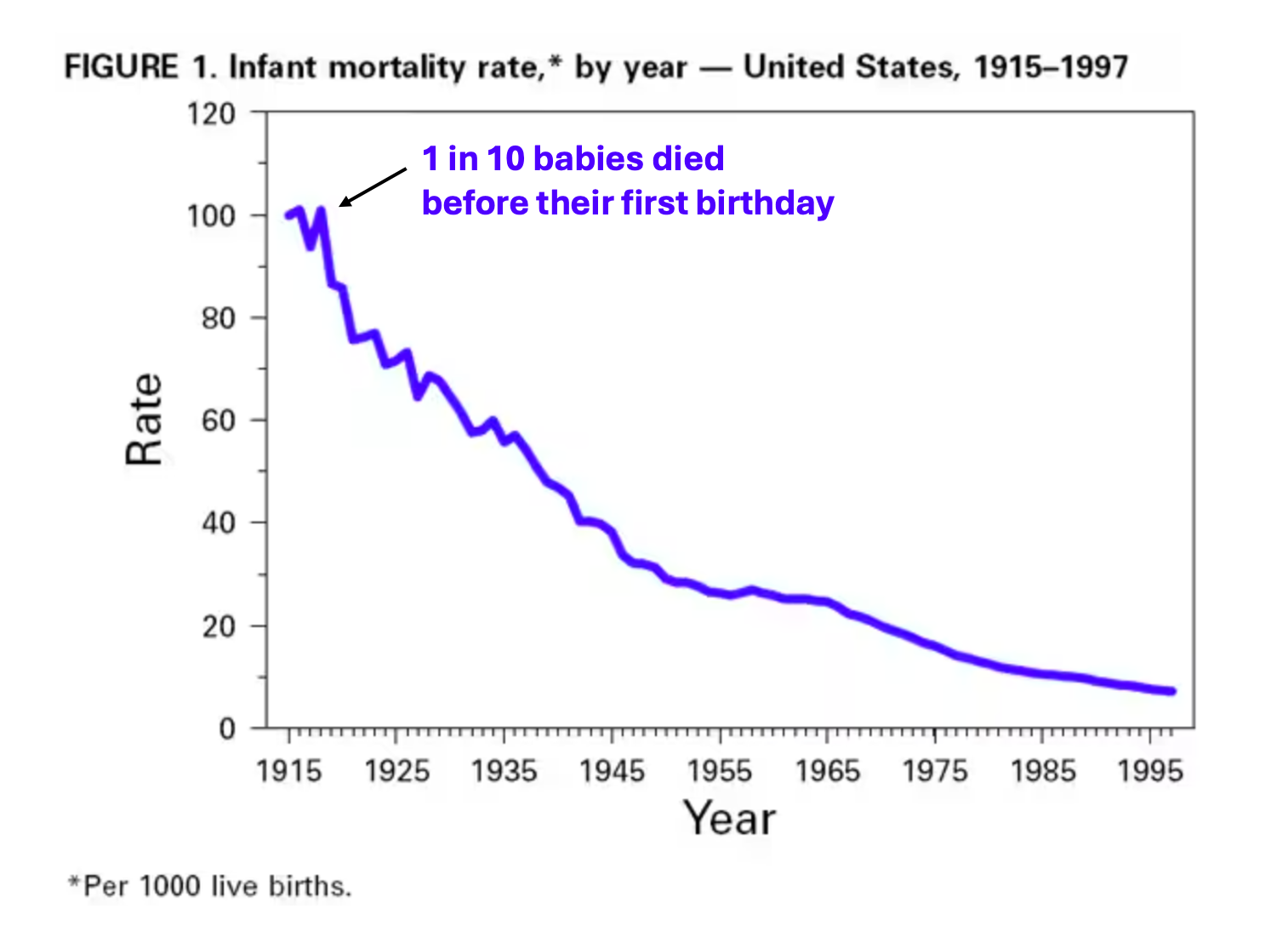

In the early 1900s in the U.S., one in ten infants would not make it to their first birthday, and 30% of all deaths in the U.S. were children younger than 5 years old, compared to less than 1% today.

For most of history, infections were the top cause of death

Infectious diseases are not our friends. For the vast majority of human history, they were by far the leading cause of death:

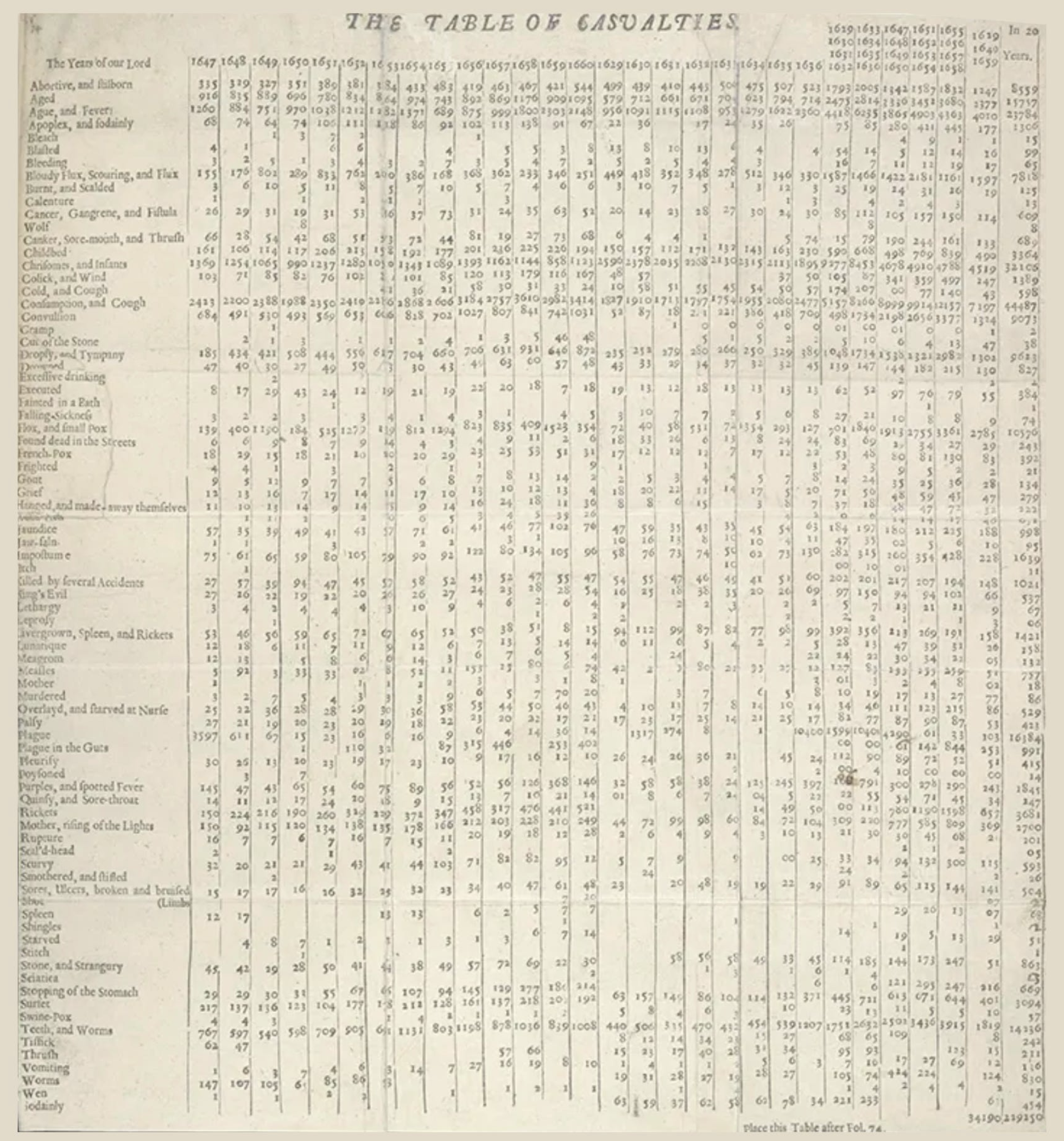

- In the medieval era, aside from deaths only categorized by age (infants and “aged”), the top categories of death were overwhelmingly infectious diseases, including tuberculosis, “fevers,” and leprosy.

- In 17th century London, “consumption and cough” was the leading cause of death (consumption describes “wasting away” diseases and was later used to describe tuberculosis primarily), followed by “chrisomes and infants” (childhood deaths), “ague and fever” (fever/chills), and “plague.”

- In 1900 in the U.S., infectious diseases were still the top killer overall (pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diarrhea/enteritis topped the list). 40% of those deaths were in children under 5.

- At the end of the twentieth century, infectious diseases were still the most common cause of premature death worldwide.

Children today are undoubtedly healthier

Deaths from infectious diseases have plummeted with the discovery of bacteria and viruses, improved sanitation, pasteurization, the discovery of antibiotics, and the development of vaccines. Childhood mortality dropped astronomically, and life expectancy in grew by three decades in the twentieth century alone. The most dramatic increases are among children under 5 years old.

What about the hygiene hypothesis?

Towards the end of the last century, as the risk of death from infections decreased, the risk of other diseases increased, including allergies. In 1989, an epidemiologist hypothesized there may be a link. He published a study showing that children from smaller families had a higher incidence of “hay fever” (allergic disease). He postulated that children with fewer siblings may be at higher risk of allergic disease because they catch fewer childhood infections.

This became known as the “hygiene hypothesis,” which states that overly clean environments are problematic and that children must be exposed to germs to develop their immune systems.

This hypothesis was just that—a guess based on observational data. It is now 35 years old, and more data has come out that shows it wasn’t quite right.

Commensal microbes are helpful; disease-causing microbes are not

The hygiene hypothesis was right that exposure to germs matters, but it was wrong about which germs. The original paper hypothesized pathogenic (disease-causing) germs—viruses and bacteria that make kids sick—were important for immune development. While research is still ongoing, the evidence to date doesn’t support this.

Instead, the data suggest that the commensal “healthy” microbes—the good bacteria that make up our microbiomes—are beneficial.

- Early childhood exposure to microbe-rich environments like farms or pets is associated with a reduced risk of allergic problems, likely due in part to an impact on the child’s microbiome

- Viruses that make kids sick like RSV are associated with increased risk of asthma

The hygiene hypothesis identified an important link between a child’s environment (like pets, farms, etc.), their exposure to germs, and the risk of allergic disease. But it got one part wrong—children don’t need infections to be healthy, they need exposure to “good germs” supporting a healthy microbiome.

What about building “immunity?”

Finally, some argue infections are beneficial because they allow children to build immunity against infections. While having immunity is good, this does not mean infections are “healthy” or should be sought out — it's much better to not get sick in the first place. Trying to get sick so you don't get sick doesn't make sense.

Seeking immunity through infection is also risky bet. Some infections don’t provide long-term immunity (like RSV and COVID), other infections can wipe out immune memory from previous infections (like measles), and all infections carry a risk to the child. It is much better to get the immunity without getting the infection. That’s what vaccines do.

Bottom Line

Infections are not good for children. If you want to help your child's immune system, get them a puppy, not a virus.

A version of this article was originally published on Your Local Epidemiologist.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things and author of Your Local Epidemiologist’s section on Health (Mis)communication. You can find her on Instagram, Bluesky, Substack, or subscribe to her website below. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.