How a neuroscientist solved the mystery of his own long COVID

When Jeff Yau started having strange symptoms after his COVID-19 infection – numbness, tingling, and shaking – he experienced what thousands of others with long COVID have found: answers were hard to find, and treatments weren’t working.

But Dr. Jeff Yau was in a unique position: he’s a neuroscientist who runs a lab studying how nerves allow us to sense and perceive the world. He had the training, resources, and —most importantly —a strong scientific network to help him seek out answers. So when his treatments failed, Jeff turned to science to figure out why.

Here is what he found.

The beginning

When Jeff tested positive during his first (and only) COVID-19 infection in 2022, he wasn’t too concerned for his own health. Young and healthy, he knew he was low risk. “I wasn’t that frightened then,” he says, “certainly not the way I would be frightened now.”

To be safe, Jeff isolated from his wife and children. He lost his sense of smell and taste and developed a fever. Then, 36 hours later, Jeff already felt better. He assumed his experience with COVID-19 was over.

New, strange symptoms

A month later, new symptoms started to appear.

First, Jeff noticed tingling and numbness in his left hand and foot. He initially thought he had hurt himself while exercising, maybe from whiplash or a pinched nerve. When he saw his doctor, all of the tests came back normal, so he went home, expecting his symptoms to go away on their own.

“That was an interesting position to be in, of uncertainty,” Jeff says. “I had the experiences… but there was no proof that there was something wrong.”

Over the next four months, the tingling and numbness worsened and spread, until Jeff had these unpleasant sensations in both hands and feet. “It was still manageable,” he says, “just a weird annoyance.” But when Jeff developed a tremor, causing his hands to shake uncontrollably, he knew something was seriously wrong.

The first clues to an answer

Back at the doctor, testing revealed changes in Jeff’s nerve and muscle function that hadn’t been there months ago. A spinal tap, where fluid was extracted from Jeff’s spine, was the first step to unlocking the mystery of his symptoms: he had an autoimmune disorder called chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP).

In other words, his immune system, which usually fights off viruses and bacteria, was attacking his own body.

In Jeff’s case, antibodies from his immune system were attacking a fatty tissue called myelin that insulates nerve cells and allows the nerves to transmit information efficiently. When the myelin insulation is damaged, nerve cells can’t communicate well with each other or with the muscles, like when cracks and potholes break up a well-traveled road.

This explained why Jeff couldn’t feel things normally and why his hands were shaking: the messages between his limbs and brain weren’t being transmitted correctly. Jeff and his doctors still didn’t know what the antibodies were or why they were attacking, but this was the first clue to explaining his symptoms.

The treatments aren’t working

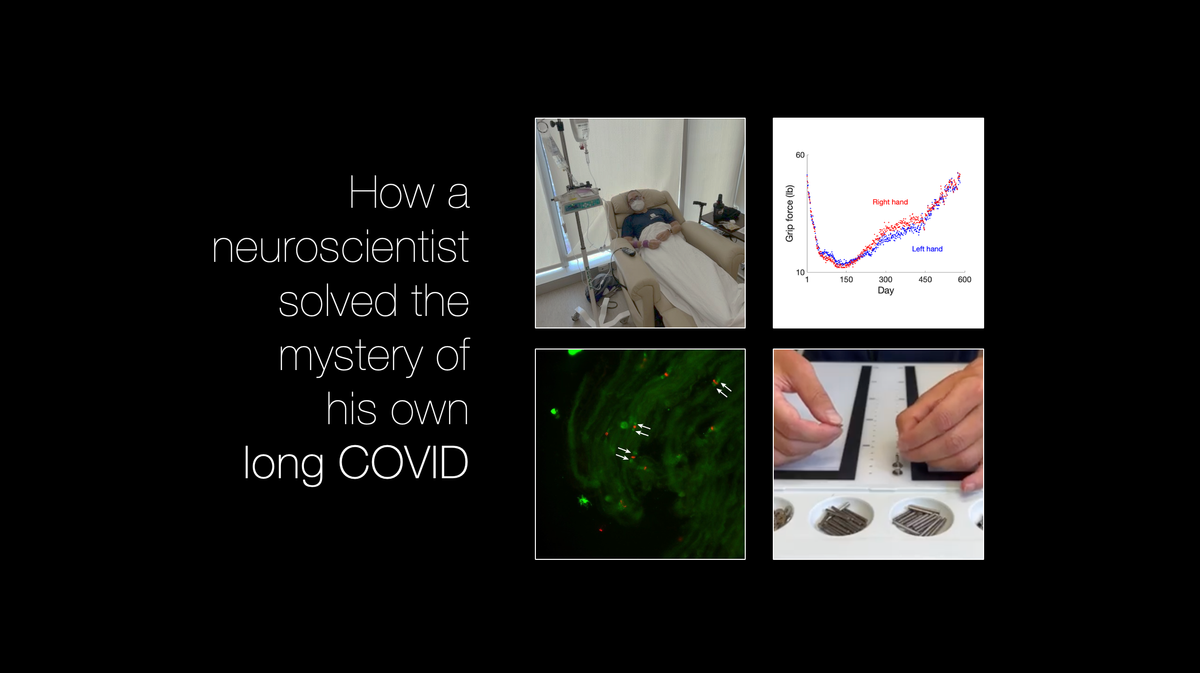

Jeff’s CIDP diagnosis began a long treatment journey, in which he underwent multiple treatment strategies, including IVIG, or intravenous immunoglobulin infusions. IVIG works by blocking the antibodies’ ability to bind to their targets, and doctors hoped it would stop Jeff’s immune system from attacking the myelin insulation.

But IVIG wasn’t working, and his symptoms worsened.

A new scientific discovery

After several failed treatments and a clinical lab test that failed to identify the antibodies that were wreaking havoc on his nerves, Jeff turned to his scientific community for help. One of Jeff’s colleagues, Dr. Matt Rasband, happens to be an expert on the nerve regions that are surrounded by myelin. Matt offered to use the tools in his lab to figure out how Jeff’s immune system was attacking the myelin and why his treatments weren’t working. Jeff accepted the offer, and a few days later, he received a text: “You have to come and see this.”

In the laboratory, Jeff looked under the microscope at rat nerve tissue that had been treated with his antibodies. Bright colors indicated where his antibodies were attacking the nerve.

“This is so amazing,” Matt said, “because even the existence of these antibodies wasn’t known until sometime within the last decade.” For both neuroscientists, the hardship of Jeff’s illness was subsumed by the excitement of scientific discovery.

“It was comforting,” says Jeff, “to be able to say: science works, science makes sense. And now that we know this, what is the next step?”

Science works

More tests revealed the identity of the antibody causing Jeff’s symptoms: an antibody that binds to neurofascin 155, which is a protein that connects the myelin insulation to the nerve. Armed with this new knowledge, Jeff searched the scientific literature for reports of CIDP patients with the neurofascin 155 variant.

Pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place: IVIG, the treatment Jeff was receiving, does not work for patients with the neurofascin 155 variant of CIDP. This is because neurofascin 155 antibodies are different from other antibodies: they can bind to myelin without using the resources that IVIG targets.

Jeff brought this information to his doctors. They decided to try plasma exchange treatment instead, which filters the blood and tends to be effective against the neurofascin 155 variant of CIDP. But despite undergoing plasma exchange every two weeks, Jeff’s symptoms kept getting worse.

Science works again

To figure out why, Jeff and Matt went back to the lab and measured Jeff’s antibody levels before and after each treatment. The measurements showed that Jeff’s neurofascin 155 antibody levels were successfully reduced the day after plasma exchange, but by the time Jeff received his next round of treatment, the levels went back up again. Plasma exchange was not reducing Jeff’s antibody levels fast enough to make a difference in his symptoms.

Equipped with new knowledge, Jeff returned to his medical team yet again, and they came up with another treatment plan. He started receiving rituximab, a drug that kills the cells that produce antibodies. Treatment with rituximab had been proven effective in other people with the neurofascin 155 variant of CIDP.

Throughout his treatments, Jeff has continued tracking his symptoms. Using equipment he already had in his laboratory, he measured the strength of his grip, his ability to perform tasks with his hands, changes in his voice, and other metrics, eventually collecting hundreds of thousands of data points over time. After beginning rituximab, the measurements are now trending upwards as his symptoms improve.

Jeff's dexterity test before (left) and after (right) starting effective treatment.

By taking advantage of his training and resources as a neuroscientist, Jeff was able to tackle the mystery of his post-COVID illness.

“I’m improving a lot now,” Jeff says, “but I don’t feel like I’m anywhere close to being back to baseline or whatever my new baseline will be.”

More research into long COVID is needed

Correlation does not equal causation, and although Jeff's symptoms showed up shortly after COVID-19 infection, it's impossible to say with certainty what caused Jeff's illness. But Jeff is not alone in his diagnosis of an autoimmune disorder after a COVID-19 infection. While the majority of people with COVID-19 do not develop an autoimmune disorder, studies have found a higher risk of autoimmune disease in people diagnosed with COVID-19 compared to people who did not have COVID-19. Furthermore, experts hypothesize that long COVID may be linked to autoimmune dysregulation.

CIDP is a rare type of autoimmune disorder that pre-dates the pandemic, with about 3 out of every 100,000 people worldwide estimated to be living with CIDP. Because CIDP is so rare, research about the disorder is limited. Experts still don’t know what causes CIDP, and there is currently not enough research to establish a definitive link between CIDP and COVID-19 infection.

This lack of research is why Dr. Jeff Yau, like many patients with post-viral syndromes, had to take matters into his own hands. When asked if he plans to publish his research on his CIDP, Jeff says, “I am definitely interested in writing this up. I want my story not to be tailored to medical experts, but instead, I want it to be more [tailored to the] general public.”

Read more about Jeff's story on Bluesky and stay tuned for part 2 of this series, an interview with Jeff on his experience with CIDP and using his training as a neuroscientist to advocate for himself within the healthcare system. Subscribe below to follow along.

Sarah Donofrio is a contributing writer for You Can Know Things. She is pursuing a Ph.D. in Neuroscience studying the role of neurodegeneration in movement disorders, and is particularly interested in how the cerebellum contributes to motor dysfunction in disease and normal aging.

This article is not intended to provide medical advice and is for informational purposes only; please consult with your physician if you have questions about medical treatments or health concerns. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of their employers or affiliated institutions.