A conversation with a neuroscientist who developed long COVID

Earlier this month, we shared the story of Dr. Jeff Yau, a neuroscientist who solved the mystery of his long COVID. A few months after his first and only COVID infection, he was diagnosed with an autoimmune disorder called chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), which means his immune system was attacking his own nerves. When his treatments weren't working, Jeff turned to science to figure out why. If you missed it, read the full story here.

The response to this story was overwhelming –it was shared all over social media and even featured in the Nature Daily Briefing. Thank you to everyone who read and shared it.

This week, we present part two of Jeff’s story: a Q&A with Jeff about his experience as a neuroscientist with long COVID. He shares what it's like to be a patient as a neuroscientist, advice for navigating the healthcare system, and how developing long COVID has changed his view of the pandemic.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Sarah: How has being a neuroscientist affected your experience with the healthcare system?

Jeff: I am trained as a scientist, so I could read the scientific literature and engage with my neurologist about that literature. When I first received my diagnosis, I spent a long time finding all the resources available and then diving deep into what was known. I became an expert on my disease, and that enabled me to have conversations with my doctors, which further earned their trust and respect.

When I went to my first neurology appointment, I had my badge on, and I was sending the implicit message, “I am a part of the system with you.” Without pushing my own credentials or knowledge base, I was still trying to get that extra respect from them. Building on that, my neurologist, once they learned what my background was, became more willing to engage with me and collaborated with me on my diagnosis and treatment, rather than dismissing me.

I’ve seen other physicians who know less about me and my background —the contrast between my interactions with those physicians compared to my neurologist becomes very clear.

Sarah: How have physicians responded to you using your scientific vocabulary to describe your symptoms?

Jeff: It varies a lot. In my experience, it boils down to whether the physician is willing to establish and change their relationship with the patient, to listen and engage in it as a more collaborative experience. I’ve almost always found that doctors start from a default position that their patients don’t know anything, and their approach would start in a more dismissive tone unless I pushed a little harder. I’ve also found that doctors are very reluctant to admit to their lack of knowledge. With physicians, I always frame things as, “You are an expert, and I might have a naïve question about something.”

Sarah: How can people without a background in science advocate for themselves in medical settings?

Jeff: Try to communicate as simply and as clearly as you can with the doctor. Science communication is hard, even for scientists. If you’re trying to communicate about areas that you’re not super familiar with, there’s the risk that you start to ramble, and there’s not really a structured discussion. But if you can very clearly and purposely speak to your physician, they can process what you’re saying. You can complement this with evidence. Being knowledgeable and educated on your own is critical.

The patient also needs to not be afraid of or shamed by their health situation. There’s this complex psychological, emotional response to being sick. There’s fear, and there’s the shame of feeling sick and weak and not who you are or who you want to be. There’s also the shame of not knowing what’s happening, and I think that mixture of emotions can cause paralysis in patients. A lot of it is being in the right mental state as a patient to realize, “I need to get help. What are my goals in this interaction with this provider?” and then making sure that those goals are clearly articulated.

Sarah: What has it been like working through the fear and shame that comes with being sick?

Jeff: For a long time, I continued to cling to this idea that I’m going to get better soon, and there was this reluctance to say, “I may be fundamentally changing from who I was.” There was a point where I was referring to my former self as “Jeff” and my sick and disabled self as “Geoff.” That was important because the more I accepted that I couldn’t just wait this out and get better, the more I realized that I needed to adjust my life to what “Geoff” needed as opposed to what “Jeff” should have been doing. By embracing the new reality, I got to a position of agency where I could start to take an active role in improving my life, as opposed to trying to keep living my life the way I used to.

Sarah: As someone who is immunocompromised, how do you feel about the state of the pandemic today?

Jeff: I have a combination of anger and fear, and the fear is not even necessarily for my own well being –even though I recognize I am at risk –but for my children and for my partner and my family and my friends. I think that they are needlessly being exposed to harms that could have been preventable. I’m angry because it could have been different. I don’t think it needed to be this way. And so when I see people dismissing the severity of COVID or dismissing the importance of wearing masks and good public health policy, I am angry about that.

Sarah: One of the common themes of the pandemic has been misinformation and deciphering what’s trustworthy. Do you have advice for determining good sources of information?

Jeff: That is really, really hard. Even now, as I follow updates on COVID, I often have to catch myself from falling into certain fallacies of saying, just because this is published, this must be right. We as scientists know that there’s a lot of questionable science that is published, and it could be published in peer reviewed journals. I don’t know that there’s a very clear answer for how to avoid that type of misinformation other than considering the type of publication —what is its impact factor, who are the researchers, do the researchers have an established history, or are they one-offs? Even for studies, if this is a case study with only one patient, that may be very different than some large-scale study that involves a hundred thousand patients. Being able to think critically about that helps me couch how much I should believe or weigh those results.

Sarah: How has your perception of COVID changed since developing CIDP?

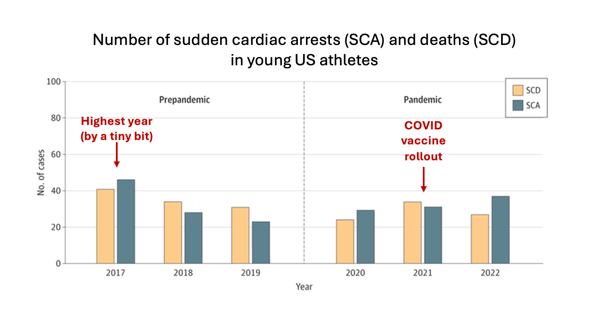

Jeff: I am much more worried about long-term sequelae, and I am much more worried about what happens for me if I get sick again, or for my family members and my friends if they get sick. I think that the long-term risks are the things that we ought to be talking about. It was just reported that the risk of developing stroke or cardiovascular dysfunction is statistically elevated up to three years after an acute infection of COVID. Also, the numbers of younger people that are having heart attacks is now clearly elevated, and I see this even in my personal circle. The hard thing, just like with my own diagnosis of CIDP, is that I can’t say this was definitively due to COVID infection, even though the timing is very much consistent. My view of COVID is let me just not get it again.

Read the story about Jeff here and learn more by following Jeff on Bluesky.

Sarah Donofrio is a contributing writer for You Can Know Things. She is pursuing a Ph.D. in Neuroscience studying the role of neurodegeneration in movement disorders, and is particularly interested in how the cerebellum contributes to motor dysfunction in disease and normal aging.

This article is not intended to provide medical advice and is for informational purposes only; please consult with your physician if you have questions about medical treatments or health concerns. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of their employers or affiliated institutions.